Pierre Nora’s concept of lieux de mémoire (sites of memory) has become a foundational framework in the fields of memory studies, cultural history, and heritage studies. Emerging from the tension between memory and history, these sites serve as repositories of collective memory in a modern era characterized by the erosion of lived memory. An examination of the theoretical foundations of lieux de mémoire is attempted, their manifestations in cultural and physical forms, and their broader implications for identity, historiography, and politics. By interrogating the concept through examples and critiques, this “study” illuminates the enduring relevance of Nora’s work in understanding the mechanisms of collective memory in a globalized and fragmented world.

Beginning this endeavour, the concept of lieux de mémoire was introduced by the French historian Pierre Nora in his multi-volume work Les Lieux de Mémoire (1984-1992). Nora’s project was rooted in the observation that modernity had fundamentally transformed the ways societies remember and engage with their past. In an era where the organic, communal process of memory—what he termed milieux de mémoire (environments of memory)—was giving way to the formalization of history, lieux de mémoire emerged as sites where memory is consciously preserved, institutionalized, and sometimes contested. Nora’s work has profound implications for understanding how collective memory operates in modern societies. These sites—physical, symbolic, or cultural—act as anchors in a rapidly changing world, providing continuity and identity in the face of historical rupture.

Central to Nora’s concept is the distinction between memory and history. Memory, in his framework, is a dynamic, lived process deeply embedded in the collective consciousness of a community. It is inherently fluid, tied to identity, and constantly reshaped by the present. History, by contrast, is a systematic, analytical reconstruction of the past that seeks objectivity and distance. While memory is experienced and shared, history is studied and recorded.

Nora argues that the advent of modernity, with its emphasis on rationality, progress, and individualism, has disrupted the traditional forms of collective memory. The communal spaces and practices that once sustained memory have been replaced by the written word, archives, and institutions of history. In this context, lieux de mémoire emerge as deliberate attempts to preserve and commemorate the past in the absence of living memory.

And so, Lieux de mémoire can take various forms, ranging from physical monuments to symbolic practices. Nora categorizes these manifestations into three broad types: material, functional, and symbolic.

Material Sites

Physical structures such as monuments, memorials, and museums are the most tangible examples of lieux de mémoire. For instance, the Arc de Triomphe in Paris serves as a testament to French military history and national pride. Similarly, the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial in Poland anchors the collective memory of the Holocaust, serving both as a site of mourning and education.

Functional Practices

Rituals, ceremonies, and commemorative events function as lieux de mémoire by embodying and transmitting shared cultural values. National holidays, such as Bastille Day in France, commemorate historical milestones and reinforce collective identity through repetition and participation.

Symbolic Representations

Symbols, texts, and cultural artifacts also operate as lieux de mémoire. Literature, anthems, and flags encapsulate collective experiences and ideals. For example, La Marseillaise, the French national anthem, is a powerful symbol of revolutionary fervor and national unity.

As such, Lieux de mémoire play a critical role in shaping and sustaining collective identity. By anchoring memory in concrete forms, these sites provide a sense of continuity in an ever-changing world. They serve as focal points for communities to reflect on their shared past, fostering a sense of belonging and cultural cohesion. As sites where collective memory is institutionalized, lieux de mémoire are inherently political. They reflect the values, priorities, and ideologies of those who create and maintain them. Governments and institutions often leverage these sites to legitimize their authority or promote specific historical narratives. For instance, the preservation of colonial monuments can perpetuate contested narratives, sparking debates about historical justice and representation. In an already globalized world, the concept of lieux de mémoire faces new challenges. The proliferation of digital technologies and transnational flows of culture complicate the notion of memory as tied to specific locations. Virtual memorials and online archives, for example, create new forms of lieux de mémoire that transcend physical boundaries. However, these developments also risk fragmenting collective memory, as diverse groups construct competing narratives in the digital sphere.

In conclusion, Pierre Nora’s concept of lieux de mémoire offers a powerful lens for understanding the mechanisms of collective memory in modern societies. These sites, whether physical, functional, or symbolic, serve as anchors of identity and continuity in an era marked by historical rupture and rapid change. However, their inherent politicization and the challenges posed by globalization and digitalization demand ongoing critical engagement. As societies continue to grapple with the complexities of memory and history, lieux de mémoire remain central to debates about identity, heritage, and the politics of commemoration. By interrogating their creation, function, and implications, we gain deeper insight into how communities remember, reinterpret, and negotiate their pasts in an ever-evolving world.

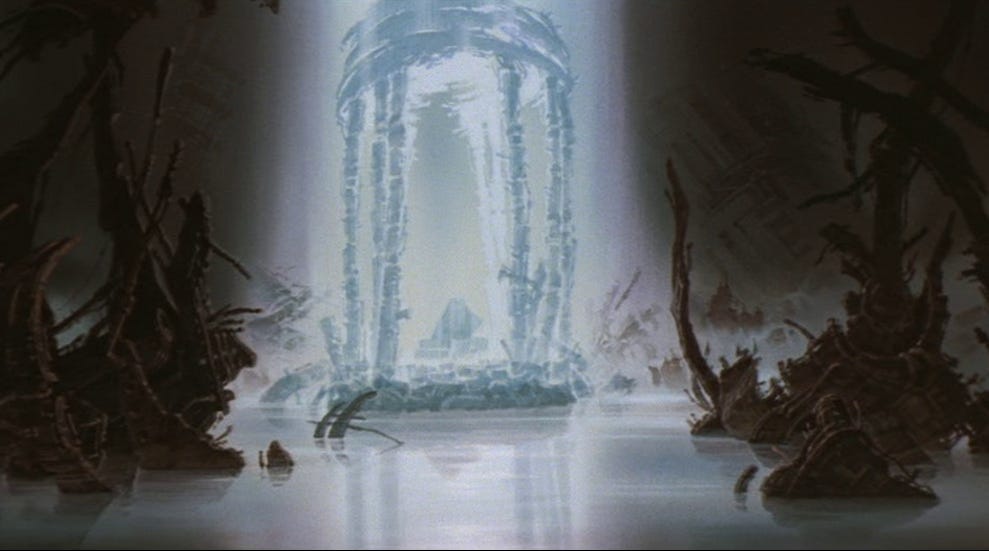

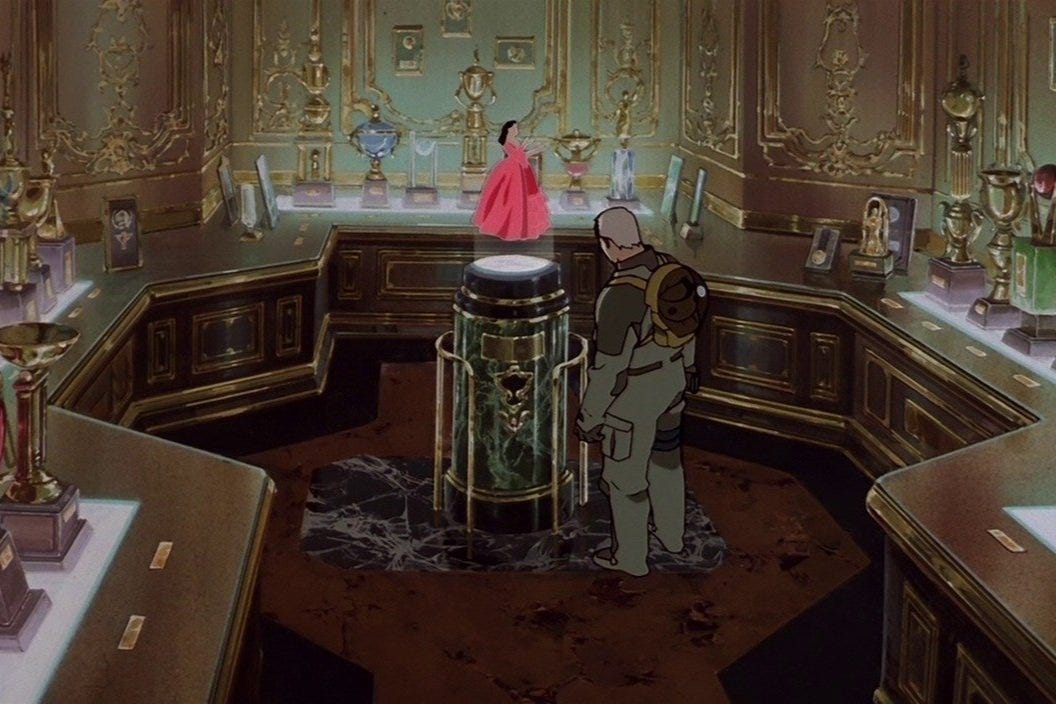

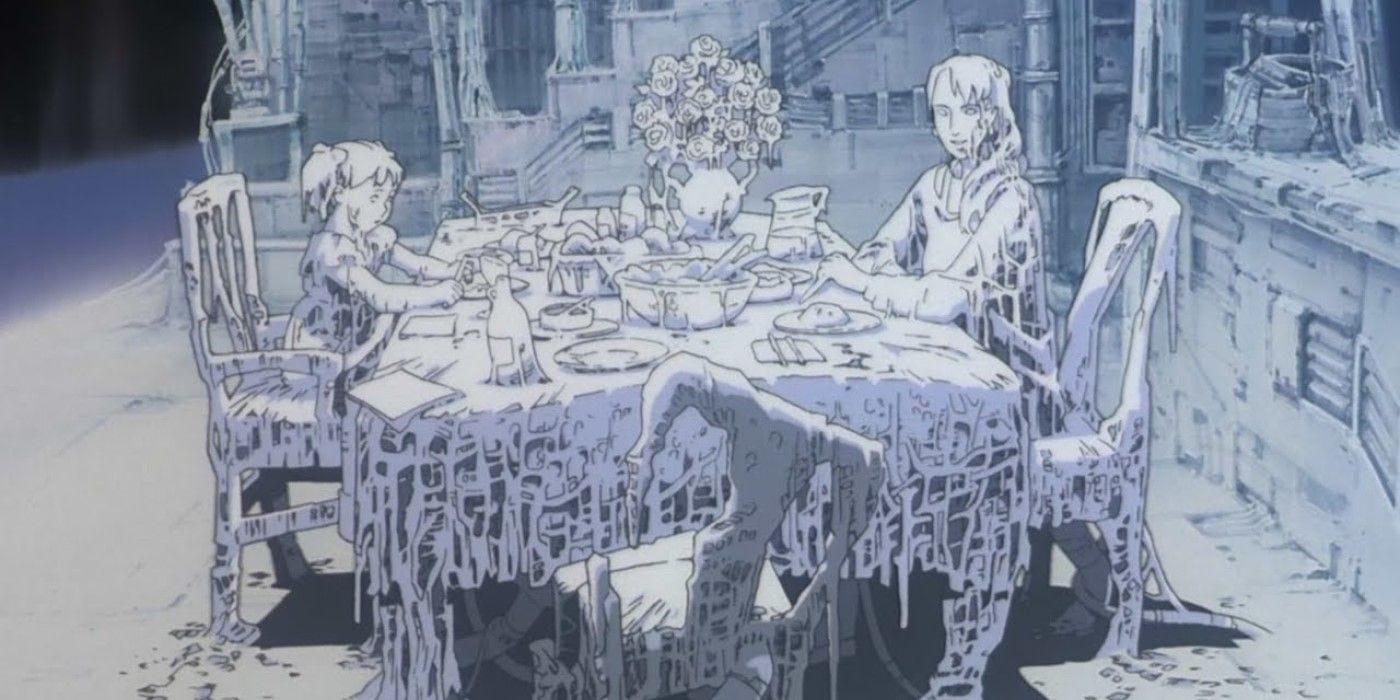

***Throughout this essay you will find movie stills from the first segment of Katsuhiro Otomo’s anthology feature Memories, called Magnetic Rose. Magnetic Rose explores the fragile nature of memory—how it defines us, how it imprisons us, and how far one might go to protect an idealized version of the past. Eva’s character, mournful and tragic, is consumed by her memories, clutching at them so tightly that they become her undoing. Her refusal to release the past distorts her reality, trapping not only herself but anyone who dares to venture too close. The film serves as a sharp critique of this obsession with an artificial world, suggesting that real growth, real healing, can only come from facing the painful truths we try to bury.

Nora, Pierre. Realms of Memory: Rethinking the French Past. Edited by Lawrence D. Kritzman, translated by Arthur Goldhammer, Columbia University Press, 1996.

Nora, Pierre. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire.” Representations, vol. 26, 1989, pp. 7-24.

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. Basic Books, 2001.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso, 2006.

Erll, Astrid. Memory in Culture. Translated by Sara B. Young, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press, 2006.

Assmann, Jan, and John Czaplicka. “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity.” New German Critique, no. 65, 1995, pp. 125-133.